INSTAGRAM CENSORSHIP

SARAH CASCONE

Increasingly, life as an artist in the 21st century means you need to be on Instagram, promoting your work, engaging with fans and potential collectors, and building that all-important follower count. But society’s growing reliance on this visual social media platform presents challenges for artists whose work doesn’t meet Instagram’s community guidelines.

Curator Jac Lahav has witnessed the struggles that these artists have trying to conform to Instagram’s rules—moderators delete posts and erase accounts, even when the content appears to match the letter of the law, which permits nudity in painting and sculpture.

“Instagram’s policies seem to be a moving target,” says Lahav. “They seem to be changing all the time and not be consistent.”

As the art world was forced to relocate online in response to the global health crisis, Lahav was inspired to create a virtual exhibition responding to Instagram’s art censorship for 42 Social Club, the project space he runs with wife Nora Leech at their home in Lyme, Connecticut.

“Instagram’s Shadow” offers a fascinating overview of some of the many ways that artists have run afoul of Instagram overlords. Censorship strikes in many ways, but its effects are always negative for artists.

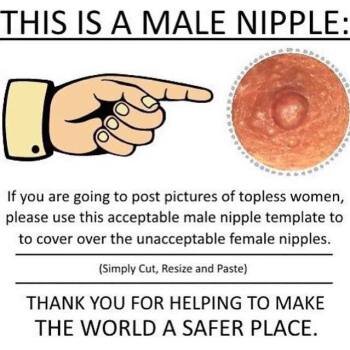

The 17 artists in the show range from celebrated feminist painter Betty Tompkins, who has faced reprobation for decades for her sexually explicit “Fuck Paintings,” as well as recent Instagram censorship, to emerging figures like Shona McAndrew, who features plus-sized nude women in her paintings and sculptures, and Micole Hebron, who pointedly targets the double standard over male nipples—allowed—and female nipples—considered sexually explicit—by creating male nipple censor shields to render women’s nipple acceptable for the app.

Instagram’s puritanical approach to nudity in art undoubtedly perpetuates the sexualization of the female body. It is also limiting artistic expression.

Artists are unable to post their real work on Instagram, the place where they are most likely to expand their reach. That proved problematic for Sara Jimenez, who received an offer to participate in a government-sponsored exhibition from someone who spotted her on Instagram. Her self censorship has kept her from attracting unwelcome attention from Instagram, but it also meant that the curator didn’t fully understand that Jimenez incorporates full-body nudity in her digitally manipulated photography, making it difficult for her to meet the expectations of the conservative community hosting the show.

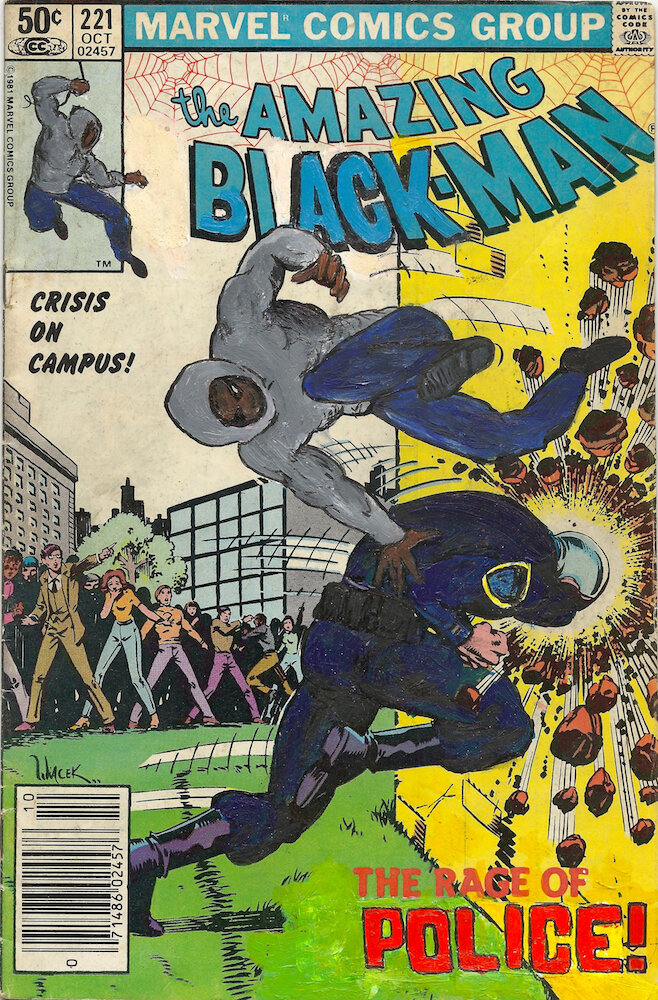

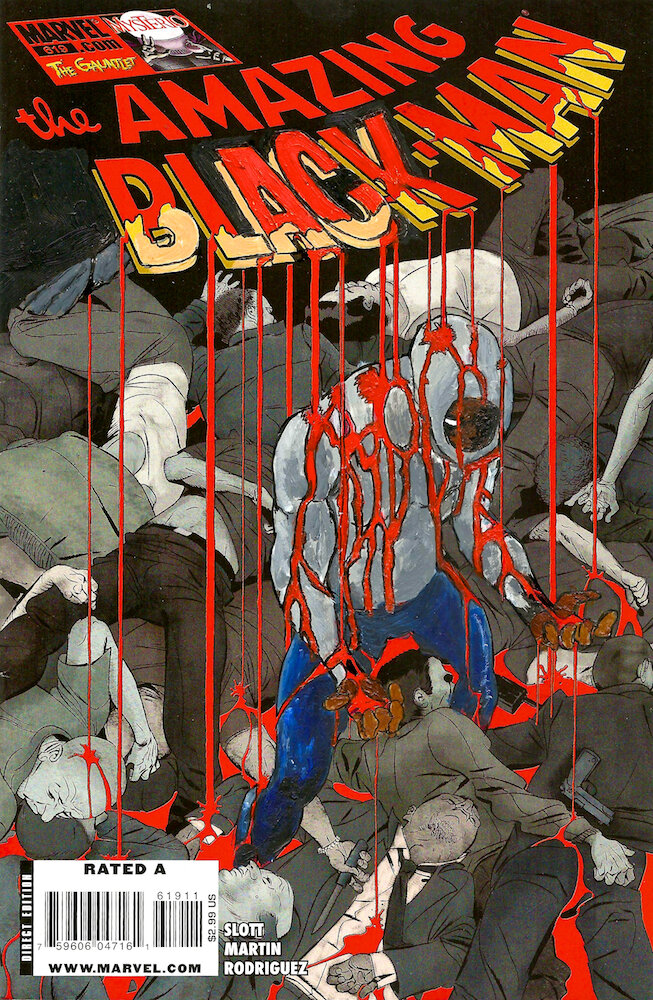

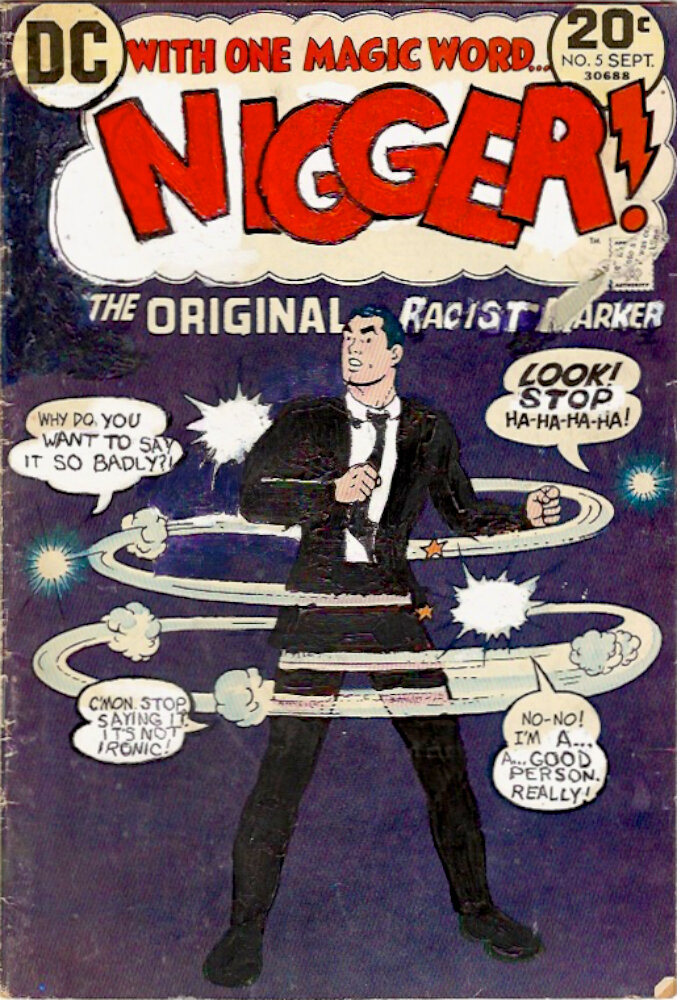

And the issue goes beyond body politics. Kumasi Barnett, whose “Amazing Black Man” works were one of the highlights of the Armory Show—the last major US art event before the pandemic sent the country into lockdown—transforms familiar superheroes into more complicated black figures by altering the covers of original Marvel comic books. But in addition to outfitting his protagonists in hoodies in jeans, instead of spandex suits, Barnett also reclaims racist slurs.

Ahead of his big Armory Show moment, Barnett actually was targeted by an Instagram ad suggesting he promote his work on the app. But when he attempted to pay for the advertising opportunity, Instagram informed the artist that his use of racial slurs was a violation of community guidelines—even though the art hopes to engage viewers in a dialogue about the negative implications of racial stereotypes and offensive, outdated language.

The show’s title, “Instagram’s Shadow,” is a nod to Instagram’s practice of “shadow banning” users and content that technically avoids violating community guidelines, but which app monitors still deem sexually suggestive. That means that certain posts won’t show up when searching on the explore page.

Instagram refuses to acknowledge the term “shadow ban,” but does admit that it restricts potentially “inappropriate” imagery in search results. When that happens, it prevents artists from reaching new audiences. These nebulous, poorly defined restrictions can be enforced differently at different times and for different users—a celebrity’s racy, barely-censored photographs can rack up tens of thousands of likes, while a similarly risqué post from an artist gets taken offline.

And the stakes are even higher for already-marginalized groups who rely on social media to share their stories with a wider audience, such as the LGBTQ community.

Tiffany Saint Bunny’s Instagram art project @TruckSlutsMag is dedicated to countering stereotypes of the all-American alpha male truck owner, often tinged with white supremacy, with images of queer and non-gendering conforming people with trucks. But Bunny has repeatedly seen her posts removed from Instagram, even when her subjects are fully clothed. And when @TruckSlutsMag community members have had their accounts deleted, they have lost entire archives of queer imagery.

For some, Instagram is the only platform where it is possible to connect with the general public. But that platform is constantly under threat of censorship—or worse, deletion.

“The key words,” says Lahav, “are fear and anxiety.”